Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a quintessential autoimmune syndrome once thought to be rare in Africans.1,2 It affects every organ and tissue, synchronously or asynchronously. The complex mosaic of pathophysiologic pathways converging into SLE phenotype is influenced by diverse factors, including the patient’s genetic predisposition, environmental triggers, and hormones, resulting in diverse clinical manifestations and ways of organ involvement.3–6

Literature is replete with reports of seizures accompanying the diagnosis of SLE, with prevalence ranging from 9.5% in Iran to 42.4% in Nigeria.7–10 In most of these reviews and case reports, the diagnosis of NPSLE rarely preceded that of SLE. In such cases, the possibility of drug-induced lupus-like syndrome should be investigated and ruled out before considering treatment with anti-seizure medication.11 We present a case of a 19-year-old woman with adult-onset seizures, which preceded the overt clinico-laboratory features of anti-dsDNA-negative SLE.

Case Report

A 19-year-old woman was presented to the neurology outpatient clinic on account of new-onset seizures, described as focal to bilateral tonic-clonic involvement of the limbs. The seizures started with right-sided facial twitches and jerky movements of the right hand. This was followed by abnormal breathing and phonation, eventually culminating in generalized tonic-clonic convulsions lasting 2–3 minutes. There was ensuing postictal sleep lasting approximately 15 minutes. There was also upward rolling of the eyes, teeth clenching, but no tongue biting, excessive salivation, or sphincteric disturbance. She had four episodes before the initial review and had no headaches or premonitory aura. Before the onset of the current symptoms, she had a brief nonspecific febrile illness that was treated empirically with parenteral artemether, though the blood film was negative for malaria parasite. There was no accompanying neck stiffness, light or sound hypersensitivity.

There was no personal or family history of epilepsy, childhood febrile seizures, head trauma, intercurrent central nervous system infections, or previous stroke. There were no motor and sensory deficits, visual disturbances, behavioral changes, or cognitive or gait impairment. There was no photosensitive skin rash, joint pain, weight loss, or drenching night sweat. The patient had no history to suggest renal or hepatic decompensation. She did not consume alcohol, psychoactive substances, or tobacco. Examination of the skin and integuments showed no unusual skin growths, ash-leaf spots, Shagreen patches, or facial port-wine staining. The neurologic examination results were not remarkable.

The blood report showed leukocyte count of 5530/uL (neutrophils = 48.3%; lymphocytes = 39.4%; platelets = 378 000/uL). Repeat test for malaria parasite was negative and the urinalysis was normal. Serum calcium, uric acid, electrolytes, urea, creatinine, and liver enzymes were normal, but serum albumin level was low (2.8 g/dL). Urinalysis showed sediments, leucocytes+++, squamous epithelial cells++, and bacteria++, while urine culture was sterile.

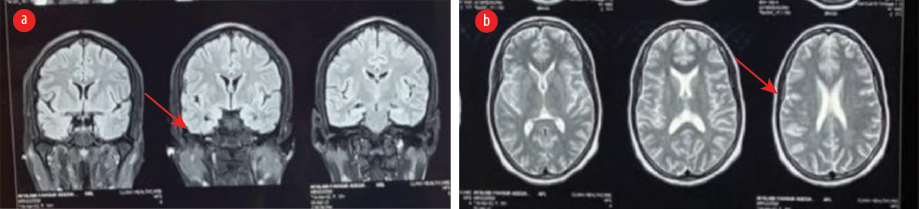

The patient was prescribed oral carbamazepine 400 mg twice daily (BD) for seizures. However, two weeks later, she returned and reported experiencing two new seizure episodes, despite her medication compliance. An assessment of breakthrough seizures was made. Carbamazepine was stopped and switched to levetiracetam 500 mg twice daily. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed a few T2/FLAIR sub-centimeter white matter hyperintensities [Figure 1]. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 50 mm in the first hour.

Figure 1: MRI of the brain show (a) normal mesial temporal lobe (arrow) in the fluid attenuated inversion recovery coronal image, and (b) white matter hypointensities (arrow) in the T2-weighted sequence.

Figure 1: MRI of the brain show (a) normal mesial temporal lobe (arrow) in the fluid attenuated inversion recovery coronal image, and (b) white matter hypointensities (arrow) in the T2-weighted sequence.

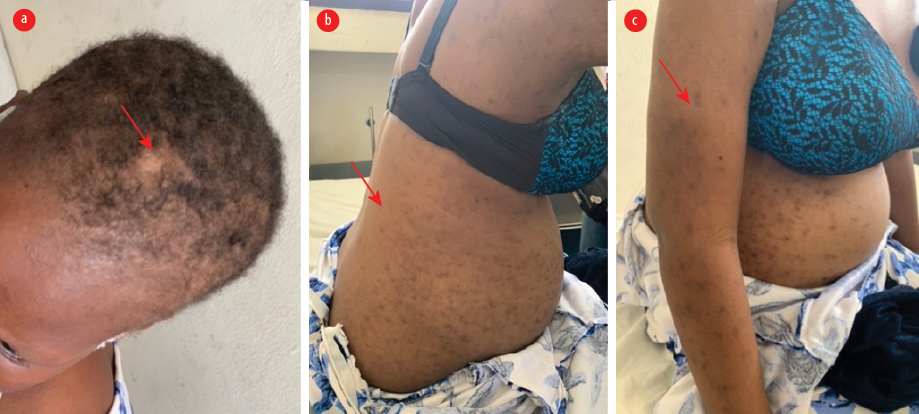

Breakthrough seizures did not recur thereafter. Three months later, the patient presented again with complaints of exertional fatigue, breathlessness, worsening malaise, anorexia, and abdominal swelling. She also reported a brief episode of irrational behavior and aimless wandering. Neurologic examination was normal except for mild asterixis. Physical examination showed periorbital swelling and multiple well-circumscribed oval-to-round hyperpigmented maculopapular non-itchy skin rashes on the trunk and proximal extremities [Figure 2]. There was a malar (butterfly) rash that spread the nasolabial fold, as well as scarring alopecia [Figure 2]. Also noted were epigastric tenderness, abdominal swelling, and ascites. Urinalysis revealed sediments, and elevated urea and creatinine. Repeat erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 150 mm in the first hour. Serum anti-nuclear antibodies were 1:640 with low complement (C3, C4) levels. Anti-dsDNA and anti-histone antibody assays were negative. Cerebrospinal fluid was normal.

Figure 2: Cutaneous manifestations, three months after initial review. (a) The scalp shows scarring alopecia. (b and c) Multiple well-circumscribed oval-round hyperpigmented macules and patches on the trunk and abdomen and proximal extremities.

Figure 2: Cutaneous manifestations, three months after initial review. (a) The scalp shows scarring alopecia. (b and c) Multiple well-circumscribed oval-round hyperpigmented macules and patches on the trunk and abdomen and proximal extremities.

The patient was diagnosed with SLE and worsening renal function (uremia) secondary to lupus nephritis, and was managed conservatively.

In the subsequent months, the patient developed further target-organ involvement, indicating disease progression. Abdominal and pelvic ultrasound revealed a right kidney size of 109 × 54 mm and left kidney size of 127 × 65 mm, loss of corticomedullary differentiation, ascites, and bilateral pleural effusion, suggestive of pan-serositis. Urinalysis showed blood 3+ and protein 3+. She was admitted and treated initially with pulse methylprednisolone, then switched to oral prednisolone, mycophenolate mofetil, and hydroxychloroquine. She developed angioedema to mycophenolate mofetil, the regimen was switched to azathioprine.

Months later, the patient experienced worsening ascites and respiratory difficulty (due to diaphragmatic splinting) along with persistently low albumin levels. She is currently on disease-modifying anti-SLE medications and remains seizure-free.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and its images.

Discussion

This case was diagnosed using the 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology (EULAR-ACR) criteria for SLE.12 Our patient satisfied the entry criterion of antinuclear antibody = > 1:80 (1:640) as well as the clinical and immunologic criteria. The constitutional symptoms of fever/malaise, neuropsychiatric features, mucocutaneous manifestation (scarring alopecia; score 2), serositis (ascites and pleural effusion; score 5), renal manifestations with 3+ proteinuria, and immunologic domains with low C3 and C4, together gave a total score of 10.

The negative anti-dsDNA result was a highlight of this case and raised early concerns for drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DILE).13 While some antimalarials, such as quinine, are known to cause DILE, carbamazepine is rarely implicated.14–16 Our patient had a three-day course of artemether, which is not known to cause DILE, and she did not receive quinine. She was given carbamazepine only two weeks before switching to levetiracetam, but her symptoms did not improve, thereby substantially weakening the case for carbamazepine induced SLE. In addition, pan-serositis, renal compromise, and hematologic findings are rare in DILE.17

Furthermore, DILE is rarely seen in young black Africans, who are more susceptible to idiopathic SLE. In addition, carbamazepine is not a well-recognized cause of DILE. Also, our attempt to use Naranjo algorithm to estimate possible causal relationship between carbamazepine and SLE yielded ‘doubtful’ results.18 Lastly, DILE is not typically associated with severe SLE.11

A systematic review of 1250 rheumatology cases in Nigeria found a 5.25% prevalence of SLE with a 95.5% female preponderance, with a mean presentation age of 33 years.2 Though neuropsychiatric presentations were common, they did not precede SLE diagnosis, as was also found in this case. In a follow up review by the same authors, 51.6% of Nigerian SLE patients had features of NPSLE. Headache was the most common symptoms (66.6%) followed by seizures (42.4%) and psychosis (30.3%).7 Our patient had behavioral symptoms, such as brief episodes of irrational behavior and aimless wandering. These were attributed to uremic encephalopathy, as she had clinical asterixis and deranged renal biochemical parameters.

Our patient experienced adult-onset seizures months before the overt clinical features of SLE. In an Iranian study on 146 children with SLE, 28% had NPSLE. Among these, 43.9% presented with neuropsychiatric symptoms at the time of SLE diagnosis, 24.4% developed these symptoms within a year, and 31.7% after a year.8 It is important to note that in this study, neuropsychiatric symptoms did not precede the onset of SLE symptoms.

Seizures were a prominent neurological symptom in our patient. In a long-term follow-up study on SLE patients with epileptic seizures, 13.6% had seizures at the onset of SLE symptoms, while the remaining 68.3% developed seizures after SLE onset.19 In a review of factors associated with time-to-seizure occurrence at or after SLE diagnosis, younger age and disease activity were independent predictors of a shorter time-to-seizure occurrence; antimalarials appeared to play a protective role against seizures.20 Our patient was young and had received antimalarials. She also had high disease activity evidenced by the low complement levels.

Neuropsychiatric SLE has been associated with specific autoantibodies,19 which is important, as our patient tested negative for anti-dsDNA antibodies. In a large single-center study, serositis was found more frequently in anti-dsDNA negative SLE patients (82.3%) compared to those who were anti-dsDNA positive.21 A similar finding was demonstrated in our patient who developed refractory ascites and pleural effusion that required drainage.

The low serum albumin in our patient was indicative of the underlying inflammatory process. Immune-complex mediated small vessel vasculitis in SLE helps explain her myriad systemic inflammatory manifestations involving the skin, joints, renal, hematologic, and neurologic systems.

Conclusion

Among indigenous Africans, idiopathic SLE should be excluded as potential cause of adult-onset seizures. In the absence of clear offending agents, metabolic or structural disease, screening with antinuclear antibody is helpful in the diagnostic evaluation of such patients as anti-dsDNA may be negative.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

references

- 1. Fava A, Petri M. Systemic lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and clinical management. J Autoimmun 2019 Jan;96:1-13.

- 2. Adelowo OO, Oguntona SA. Pattern of systemic lupus erythematosus among Nigerians. Clin Rheumatol 2009 Jun;28(6):699-703.

- 3. Abdulla E, Al-Zakwani I, Baddar S, Abdwani R. Extent of subclinical pulmonary involvement in childhood onset systemic lupus erythematosus in the Sultanate of Oman. Oman Med J 2012 Jan;27(1):36-39.

- 4. Hanly JG, Urowitz MB, Sanchez-Guerrero J, Bae SC, Gordon C, Wallace DJ, et al; Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics. Neuropsychiatric events at the time of diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus: an international inception cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2007 Jan;56(1):265-273.

- 5. The American College of Rheumatology nomenclature and case definitions for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes. Arthritis Rheum 1999 Apr;42(4):599-608.

- 6. Nived O, Sturfelt G, Liang MH, De Pablo P. The ACR nomenclature for CNS lupus revisited. Lupus 2003;12(12):872-876.

- 7. Adelowo OO, Oguntona AS, Ojo O. Neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus among Nigerians. Afr J Med Med Sci 2009 Mar;38(1):33-38.

- 8. Khajezadeh MA, Zamani G, Moazzami B, Nagahi Z, Mousavi-Torshizi M, Ziaee V. Neuropsychiatric involvement in juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Neurol Res Int 2018 May;2018:2548142.

- 9. Ojo O, Omisore-Bakare M. Neuropsychiatric lupus in a Nigerian teenager. African Journal of Rheumatology 2018 Apr;6(1):23-25.

- 10. İncecik F, Hergüner MÖ, Yilmaz M, Altunbaşak Ş. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with status epilepticus: a case report. Turk J Rheumatol 2012;27(3):205-207.

- 11. Vaglio A, Grayson PC, Fenaroli P, Gianfreda D, Boccaletti V, Ghiggeri GM, et al. Drug-induced lupus: traditional and new concepts. Autoimmun Rev 2018 Sep;17(9):912-918.

- 12. Aringer M, Costenbader KH, Daikh DI, Brinks R, Mosca M, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. 2019 EULAR/ACR classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71(9):1400-1412.

- 13. Laurinaviciene R, Sandholdt LH, Bygum A. Drug-induced cutaneous lupus erythematosus: 88 new cases. Eur J Dermatol 2017 Feb;27(1):28-33.

- 14. Vedove CD, Del Giglio M, Schena D, Girolomoni G. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Res 2009 Jan;301(1):99-105.

- 15. Katz U, Zandman-Goddard G. Drug-induced lupus: an update. Autoimmun Rev 2010 Nov;10(1):46-50.

- 16. Sarkar R, Paul R, Pandey R, Roy D, Sau TJ, Mani A, et al. Drug-induced lupus presenting with myocarditis. J Assoc Physicians India 2017 Jun;65(6):110.

- 17. Solhjoo M, Goyal A, Chauhan K. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- 18. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981 Aug;30(2):239-245.

- 19. Appenzeller S, Cendes F, Costallat LT. Epileptic seizures in systemic lupus erythematosus. Neurology 2004 Nov;63(10):1808-1812.

- 20. Andrade RM, Alarcón GS, González LA, Fernández M, Apte M, Vilá LM, et al; LUMINA Study Group. Seizures in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: data from LUMINA, a multiethnic cohort (LUMINA LIV). Ann Rheum Dis 2008 Jun;67(6):829-834.

- 21. Conti F, Ceccarelli F, Perricone C, Massaro L, Marocchi E, Miranda F, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus with and without anti-dsdna antibodies: analysis from a large monocentric cohort. Mediators Inflamm 2015;2015:328078.