A full-term neonate was brought to the emergency department on day 20 of life with marked facial asymmetry, macrostomia, and deficient perioral musculature [Figure 1]. There was no facial nerve palsy. External ear deformities with preauricular skin tags were present, but the palate was intact. The infant showed no respiratory distress or other systemic anomalies. Initial management focused on airway assessment, assisted feeding support, and a multidisciplinary evaluation to determine syndromic associations and plan for surgical correction. Written consent was obtained from the patient's kin.

Figure 1: Day-20 neonate with a deep lateral facial cleft extending from the oral commissure to the temporal region. Note the unfused mouth angle and a distal skin tag.

Figure 1: Day-20 neonate with a deep lateral facial cleft extending from the oral commissure to the temporal region. Note the unfused mouth angle and a distal skin tag.

Question

1. What is the most likely diagnosis?

a. Goldenhar syndrome.

b. Treacher Collins syndrome.

c. Hemifacial microsomia.

d. Isolated Tessier cleft 7.

Answer

d. Isolated Tessier cleft 7.

Discussion

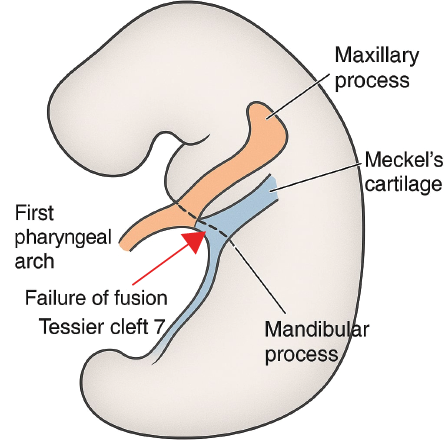

Tessier’s classification for craniofacial clefts (0–14) assigns cleft 7 to the lateral (transverse) facial cleft.1 It is a rare congenital anomaly with an incidence of approximately 1 per 80 000–300 000 live births.2 It affects the oral commissure and extends toward the ear or temporal region. It results from a developmental failure of fusion between the maxillary and mandibular processes of the first branchial arch during the fifth week of intrauterine life [Figure 2]. As the first and second pharyngeal arches contribute to facial development, their improper fusion can lead to macrostomia and associated anomalies. This defect is attributed to genetic mutations, environmental teratogens, or amniotic band disruption during early fetal development.3 Tessier cleft 7 ranges from mild macrostomia (widened mouth opening) to a deep cleft with soft-tissue and bony defects that affect facial symmetry.

Figure 2: Schematic representation of the embryology of Tessier cleft 7, illustrating the failure of fusion between the maxillary and mandibular processes of the first pharyngeal arch, leading to a lateral facial cleft.

Figure 2: Schematic representation of the embryology of Tessier cleft 7, illustrating the failure of fusion between the maxillary and mandibular processes of the first pharyngeal arch, leading to a lateral facial cleft.

Clinically, patients with Tessier cleft 7 exhibit facial asymmetry, absent or hypoplastic perioral musculature, and external ear abnormalities. Although facial nerve function is typically preserved, severe cases may present with asymmetrical facial movement. Feeding difficulties (due to poor oral seal, drooling, and risk of aspiration) are common and mandate early nutritional intervention.

Tessier cleft 7 is often associated with craniofacial syndromes. The most common associations include:

- Goldenhar syndrome (oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrum): Hemifacial microsomia, ear deformities, epibulbar dermoids, vertebral anomalies, and congenital heart defects.4

- Treacher-Collins syndrome: Zygomatic and mandibular hypoplasia, down-slanting palpebral fissures, ear anomalies, and dental malformations.4

- Hemifacial microsomia: Unilateral underdevelopment of skeletal and soft tissue, affecting facial symmetry.

- Other rare associations: Craniofacial microsomia, branchio-oto-renal syndrome, and oto-mandibular dysplasia.

Surgical correction of Tessier cleft 7 is typically performed between 3–6 months of age, depending on the severity and associated anomalies. The primary objectives of surgery are to restore oral competence, achieve facial symmetry, preserve facial nerve function, and minimize scarring.5 Various surgical techniques, including Z-plasty, straight-line closure, vermilion square flap, and soft tissue rearrangement, are employed to reconstruct the perioral musculature and align the oral commissure. In cases with bony involvement, additional maxillofacial procedures may be necessary.2,6 Postoperative management includes scar management, speech therapy, orthodontic evaluation, and regular follow-ups to monitor facial growth, dental alignment, and functional outcomes. Long-term multidisciplinary care ensures optimal aesthetic and functional rehabilitation, improving both feeding efficiency and speech development, enhancing the patient’s quality of life and psychosocial well-being.

Conclusion

Tessier cleft 7 is a rare but significant craniofacial anomaly requiring early diagnosis, multidisciplinary intervention, and tailored surgical correction. Timely feeding support, surgical repair, and long-term follow-up are essential to ensure optimal functional, aesthetic, and psychosocial outcomes.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

references

- Tessier P. Anatomical classification facial, cranio-facial and latero-facial clefts. J Maxillofac Surg 1976 Jun;4(2):69-92.

- 2. Khorasani H, Boljanovic S, Knudsen MA, Jakobsen LP. Surgical management of the Tessier 7 cleft: a review and presentation of 5 cases. JPRAS Open 2019 Jul;22:9-18.

- 3. Coleman JR Jr, Sykes JM. The embryology, classification, epidemiology, and genetics of facial clefting. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2001 Feb;9(1):1-13.

- 4. Kuriyama M, Udagawa A, Yoshimoto S, Ichinose M, Suzuki H. Tessier number 7 cleft with oblique clefts of bilateral soft palates and rare symmetric structure of zygomatic arch. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2008;61(4):447-450.

- 5. Mannali Sr AR, Pasupathy M, Kumar S. Tessier 7 cleft: clinical presentation and surgical correction in a case report. Cureus 2024 Oct;16(10):e71062.

- 6. Woods RH, Varma S, David DJ. Tessier no. 7 cleft: a new subclassification and management protocol. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008 Sep;122(3):898-905.