Sleep-related epileptic seizures and parasomnias are the two main categories of paroxysmal motor behaviors that occur during sleep.1 In 1977, Pedley and Guilleminault defined episodic nocturnal wanderings (ENWs) as an unusual form of epilepsy marked by paroxysmal ambulation and abnormal behavioral and cognitive manifestations during sleep.2 Although no nocturnal seizures had been documented, the presence of interictal discharges (IIDs) on scalp EEG and a favorable response to anti-seizure drugs (ASMs) led the authors to suggest that ENWs represent an atypical form of epilepsy.3

The epileptic nature of these episodes was questioned by Maselli et al,4 and Oswaldet al,5 who interpreted them as night terrors accompanied by sleepwalking. Several years later, Plazzi et al,6 introduced the term “epileptic nocturnal wanderings” to describe similar seizures in four patients who displayed clear epileptic discharges during normal episodic overnight wanderings. They also reported the coexistence of ENWs, nocturnal paroxysmal dystonia, and paroxysmal arousals, as well as similarities between these conditions, suggesting that they constitute a spectrum of sleep-related epilepsy.6

Although seizures are a common symptom of intracranial mass lesions, ENWs have rarely been observed in combination with obvious brain structure abnormalities.7,8 In this report, we discuss a case of a young girl with a rather unusual ENW presentation, providing evidence that supports the notion that ENWs are most likely actual epileptic seizures.

Case Report

A 14-year-old right-handed female began experiencing recurrent episodes of sleeping outside her bed at the age of 12. Occasionaly, she would venture beyond her bedroom and have no recollection of the experiences. She sometimes responded instantly to verbal prompts, and at other times needed more time to respond. She did not exhibit oral or hand automatism, eye or facial twitching, jerky gestures, or sounds, nor did she have a history of generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The parents reported paroxysmal attacks while she was ambulated and engaged in sophisticated and structured motor activities. During these episodes, the patient remained silent and would return to bed if accompanied by another person. Even though she knew that something had happened during the night, she could not provide a detailed narrative of the incidents the following day. Unfortunately, events were not recorded after her admission to the epilepsy monitoring unit.

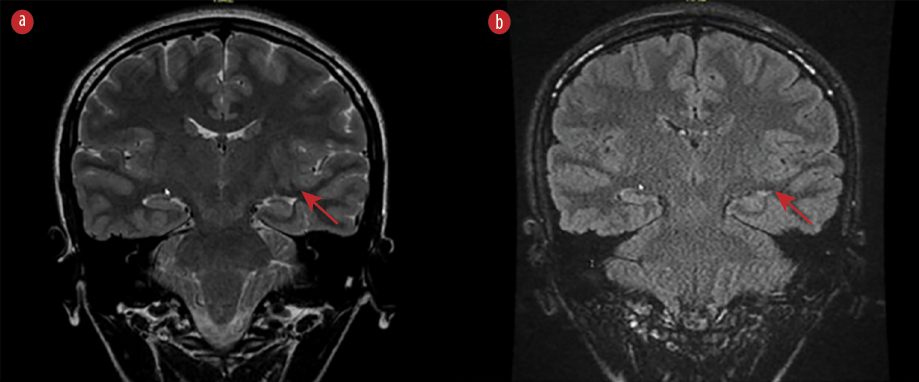

The episodes occurred with variable frequency and clustering. Approximately two and a half months before her most recent hospitalization, she started taking 500 mg of levetiracetam twice a day. During this time, her seizure frequency decreased, and she showed signs of improvement. She sustained two minor injuries outside her bedroom, and despite taking her ASM, she would be found outside her bed one or two nights per month. Stress was identified as one of the aggravating factors for these events. She had no memory of the events, and there were no other recognized risk factors in her past or family history. Her academic performance was average. Neurological examination was unremarkable, and routine laboratory tests were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed an asymmetrical smaller left temporal lobe with ill-distinct gray-white matter differentiation. Additionally, incomplete inversion of the left hippocampus was observed [Figure 1].

Figure 1: The MRI brain image (a) T2 and (b) fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences) shows an asymmetrical, smaller left temporal lobe with poorly-distinct gray-white matter differentiation. In addition, incomplete inversion of the left hippocampus (arrows) is observed.

Figure 1: The MRI brain image (a) T2 and (b) fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences) shows an asymmetrical, smaller left temporal lobe with poorly-distinct gray-white matter differentiation. In addition, incomplete inversion of the left hippocampus (arrows) is observed.

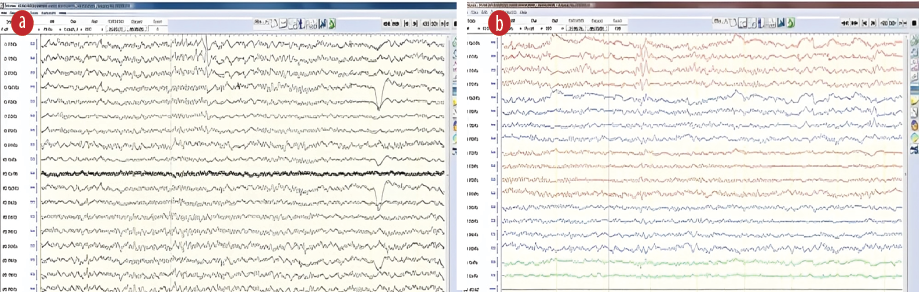

The patient was readmitted to the epilepsy monitoring unit for further classification of her seizures and treatment. Unfortunately, neither clinical nor electrographic seizures occurred during her 12-day hospitalization while of ASM. The neuropsychology and psychiatric teams evaluated her upon admission and excluded any psychiatric causes. The interictal electroencephalography (EEG) showed normal background activity and a focus of sharp-wave activity in the left temporal lobe [Figure 2]. Due to undesirable side effects, such as agitation, levetiracetam was substituted after discharge. Lamotrigine was initiated at a dose of 25 mg twice a day for three days, and the patient and her family were instructed on how to gradually increase the dose to 200 mg twice daily. When she was reassessed at the outpatient clinic three months later, she reported no recollection of any wandering episodes.

Figure 2: Interictal epileptiform discharges with sharp waves visible over the left temporal area in the (a) Cz and (b) bipolar montages.

Figure 2: Interictal epileptiform discharges with sharp waves visible over the left temporal area in the (a) Cz and (b) bipolar montages.

Discussion

ENWs, paroxysmal arousals, and NPD are some examples of diverse presentations of nighttime frontal lobe epilepsy (NFLE) presentations that have been reported.3 The major epileptogenic zone in the frontal areas may not always be easily distinguished in some cases due to ambiguous EEG ictal patterns. Initially identified as NPD in 1981, NFLE was considered a motor condition of sleep (NPD).6–9 Differentiating NPD attacks from other non-epileptic nocturnal paroxysmal events, such as parasomnias, can be challenging due to the atypical seizure semiology, onset during sleep, and often uninformative scalp EEG and brain magnetic resonance imaging.8

The diagnosis of ENWs is complicated by the presence of frontal lobe hyperactivity or hypermotor activity during epileptic events, making it difficult to pinpoint the primary epileptogenic zone in the frontal areas for most patients.9 Occasionally, the literature provides clues that suggest a potential temporal origin for sleep-related hyperkinetic seizures. Arroyo et al,10 reported the cessation of seizures in one of 23 NPD patients after the removal of an anterior temporal cavernous angioma. Recent studies have also suggested a temporal lobe origin for epileptic nocturnal wanderings, a clinical symptom of NFLE.11 Furthermore, one in four of the patients with ENWs described by Plazzi et al,6 experienced an aura characterized by a feeling of the stomach rising, a symptom more consistent with temporal lobe epilepsy than frontal lobe epilepsy.11 Focal impaired awareness seizures that predominantly or exclusively occur during sleep have been described in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. These seizures are less common and do not include hyperkinetic behavior or intricate motor automata observed in ENWs.12,13

Epileptic fugue, described during an absence or complex partial nonconvulsive status epilepticus, may occur in a postictal phase and often manifest as a frank confusional condition in patients with generalized seizures.14 In 1956, when Gastaut et al,15 described an interesting case of a prolonged fugue state. Moreover, between 1887 and 1889, while serving as professor of neurology at the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, Jean-Martin Charcot gave several conversational case presentations on general neurology where he described a case with multiple fugue states, possibly of epileptic origin.16 Jiménez-Genchi et al,17 reported the coexistence of ENWs and an arachnoid cyst in a 15-year-old boy with a left temporal lobe arachnoid cyst. Furthermore, Huang et al,1 described ENW and complex visual hallucinations in a 25-year-old man with a left anterior temporal focus.

Our reported case aligned with Pedley’s et al,2 description of ENWs that improved with ASMs in 1977, providing evidence that ENWs are localized epilepsy and respond to ASMs. Plazzi et al,6 and Provini et al,7 have indicated that ENWs can originate from the frontal, temporal, or frontotemporal areas based on IIDs and focal IIDs observed in the interictal EEG.

Identifying aberrant paroxysmal motor episodes during sleep presents a challenge for clinicians. These episodes can either be parasomnias, which are benign nonepileptic sleep disorders characterized as “unpleasant or undesirable behavioral or experiential phenomena that occur predominantly or exclusively during the sleep period,” or epileptic seizures that require testing and treatment. Parasomnias include sleepwalking and sleep terrors. Distinguishing seizures from parasomnias based on clinical history is often simple. However, ENW is becoming more widely known and presents a diagnostic dilemma.18

ENW, characterized by its peculiar complex motor pattern and positive response to ASMs, has been theorized to be an unusual form of nocturnal epilepsy. Recent studies have demonstrated that agitated somnambulant episodes associated with ENWs are connected to ictal epileptic discharges despite equivocal early EEG recordings.19

Conclusion

Epileptic nocturnal wandering is one manifestation of sleep-related hypermotor epilepsy. Clinicians should consider ENWs in the differential diagnosis of paroxysmal motor behaviors occurring during sleep. ENW is rare and thought to be an atypical form of nocturnal epilepsy that is responsive to ASMs. This case provides further evidence that ENW represents an uncommon type of nocturnal focal impaired awareness seizure. When evaluating patients with nighttime wandering not caused by epilepsy, the possibility of epilepsy should be considered.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Written consent was taken from the patient.

references

- 1. Huang YZ, Chu NS. Episodic nocturnal wandering and complex visual hallucination. A case with long-term follow-up. Seizure 1998 Feb 1;7(1):67-71.

- 2. Pedley TA, Guilleminault C. Episodic nocturnal wanderings responsive to anticonvulsant drug therapy. Ann Neurol 1977 Jul;2(1):30-35.

- 3. Nobili L, Francione S, Cardinale F, Russo GL. Epileptic nocturnal wanderings with a temporal lobe origin: a stereo-electroen-cephalographic study. Sleep 2002 Sep;25(6):659-661.

- 4. Maselli RA, Rosenberg RS, Spire JP. Episodic nocturnal wanderings in non-epileptic young patients. Sleep 1988 Mar 1;11(2):156-161.

- 5. Oswald I. Episodic nocturnal wanderings. Sleep 1989 Apr;12(2):186-188.

- 6. Plazzi G, Tinuper P, Montagna P, Provini F, Lugaresi E. Epileptic nocturnal wanderings. Sleep 1995 Nov 1;18(9):749-756.

- 7. Provini F, Plazzi G, Montagna P, Lugaresi E. The wide clinical spectrum of nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2000 Aug 1;4(4):375-386.

- 8. Tinuper P, Bisulli F. From nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy to sleep-related hypermotor epilepsy: a 35-year diagnostic challenge. Seizure 2017 Jan;44:87-92.

- 9. Kurahashi H, Hirose S. Autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy. GeneReviews. 2023 [cited 2022 August 19]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1169/.

- 10. Arroyo S, Santamaria J, Setoain JF, Lomeña F, Bargallo N, Tolosa E. Nocturnal paroxysmal dystonia related to a prerolandic dysplasia. Epilepsy Res 2001 Jan;43(1):1-9.

- 11. Nobili L, Cossu M, Mai R, Tassi L, Cardinale F, Castana L, et al. Sleep-related hyperkinetic seizures of temporal lobe origin. Neurology 2004 Feb;62(3):482-485.

- 12. Blair RD. Temporal lobe epilepsy semiology. Epilepsy Res Treat 2012;2012:751510.

- 13. Bernasconi A, Andermann F, Cendes F, Dubeau F, Andermann E, Olivier A. Nocturnal temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology 1998 Jun;50(6):1772-1777.

- 14. Das S, Ray BK, Dubey S. Temporal lobe epilepsy with nocturnal wandering leading to discovery of moyamoya angiopathy. Acta Neurologica Belgica 2023 Feb;123(1):279-281.

- 15. Gastaut H, Roger J, Roger A. The significance of certain epileptic fugues; concerning a clinical and electrical observation of temporal status epilepticus. Revue Neurologique 1956 Mar;94(3):298-301.

- 16. Goetz CG. Charcot at the Salpêtrière: ambulatory automatisms. Neurology 1987 Jun;37(6):1084-1088.

- 17. Jiménez-Genchi A, Díaz-Galviz JL, García-Reyna JC, Avila-Ordoñez MU. Coexistence of epileptic nocturnal wanderings and an arachnoid cyst. J Clin Sleep Med 2007 Jun;3(4):399-401.

- 18. Derry CP, Davey M, Johns M, Kron K, Glencross D, Marini C, et al. Distinguishing sleep disorders from seizures: diagnosing bumps in the night. Arch Neurol 2006 May;63(5):705-709.

- 19. Duffau H, Kujas M, Taillandier L. Episodic nocturnal wandering in a patient with epilepsy due to a right temporoinsular low-grade glioma: relief following resection. Case report. J Neurosurg 2006 Mar;104(3):436-439.